Saturday, 08 November 2025 01:24

Summary

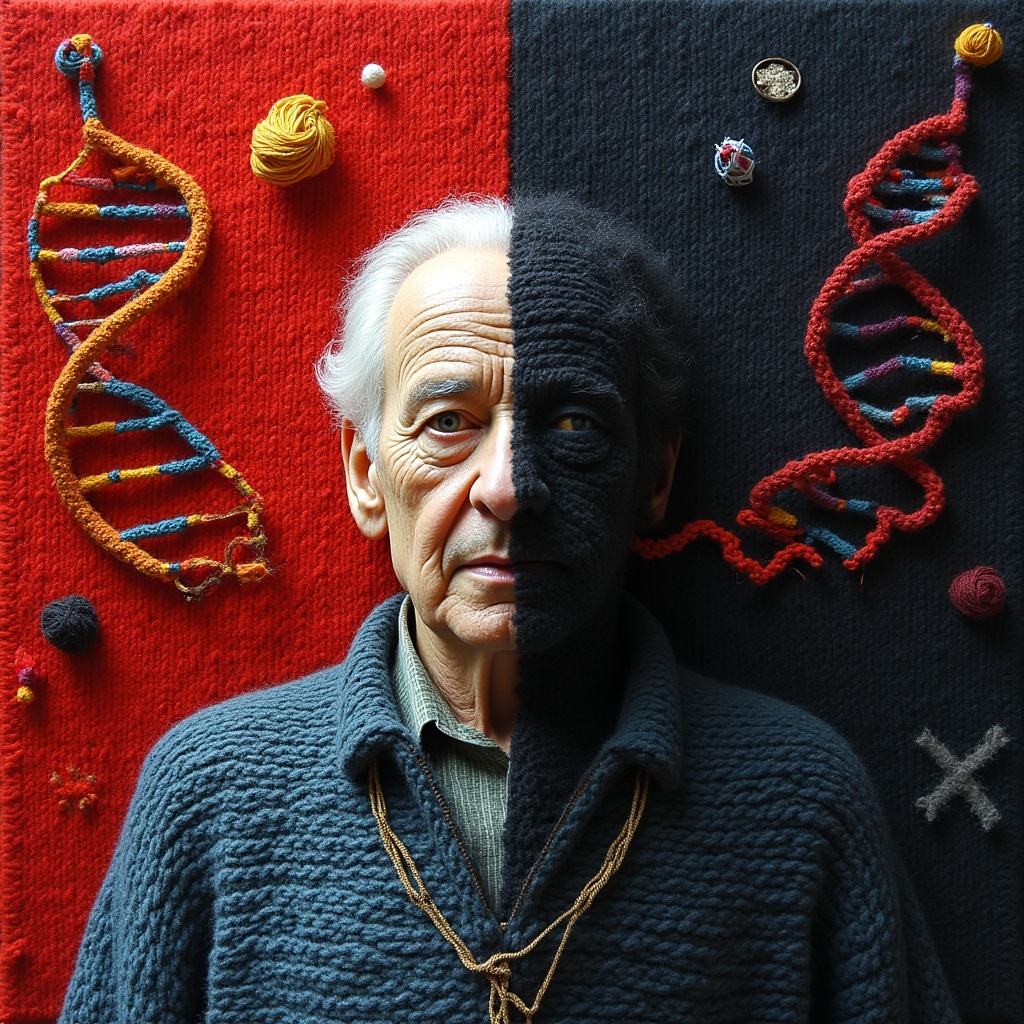

James Watson, a towering figure of twentieth-century science, has died at the age of 97. His name is inextricably linked with one of the most significant discoveries in history: the double helix structure of DNA, a breakthrough that unlocked the secrets of heredity and laid the foundations for the modern era of genetics and biotechnology. Alongside Francis Crick, he solved a puzzle that had confounded the world's greatest minds, earning a Nobel Prize in 1962 and a permanent place in the scientific pantheon. Yet, the brilliance of this achievement is shadowed by a darker, more troubling legacy. In the decades following his monumental discovery, Watson cultivated a second reputation as a purveyor of inflammatory and scientifically unfounded statements on race, intelligence, and gender. His public pronouncements grew more reckless over time, leading to a gradual but decisive fall from grace. The same scientific establishment that once celebrated him was ultimately forced to condemn and ostracise him, stripping him of honorary titles and severing institutional ties. His life presents a stark and unsettling dichotomy: a mind capable of grasping the elegant complexity of life's code, yet seemingly incapable of transcending crude and damaging prejudices. His story is not just that of a great discovery, but a cautionary tale about the complex relationship between genius, character, and accountability.

A Prodigy's Path to Cambridge

James Dewey Watson was born in Chicago, Illinois, on 6 April 1928. From an early age, he displayed a precocious intellect, a trait nurtured by a family that valued knowledge and reason. His father, a birdwatcher, instilled in him a keen interest in ornithology. This early fascination with the natural world led him to enrol at the University of Chicago at the age of just 15 under a programme for gifted youngsters. He graduated in 1947 with a degree in zoology. A pivotal moment in his intellectual development came from reading Erwin Schrödinger's 1944 book, "What is Life?", which speculated on the physical nature of the gene. The book captivated Watson, steering him towards genetics and the fundamental questions of heredity.

He pursued his doctorate at Indiana University, studying under the guidance of Salvador Luria, an Italian-born microbiologist and a key figure in the 'Phage Group', a collective of researchers studying viruses that infect bacteria. Luria would later share a Nobel Prize in 1969 for his work on genetic mutations. Watson completed his PhD in 1950 and, after a brief postdoctoral period in Copenhagen, his ambition to unravel the structure of DNA led him to England. In 1951, a conference in Naples exposed him to the work of Maurice Wilkins, a physicist at King's College London who was using X-ray diffraction to study DNA fibres. The images sparked Watson's interest, convincing him that this was the technique that could solve the puzzle. This conviction propelled him to the Cavendish Laboratory at the University of Cambridge, where he secured a position later that year. It was there that he met Francis Crick, a British physicist then working on his PhD, who shared his fervent belief that the structure of DNA was the most important scientific question of their time.

The Race for the Secret of Life

At the Cavendish Laboratory, Watson and Crick formed an immediate and powerful intellectual partnership. Despite being assigned to different projects, their shared obsession with DNA dominated their conversations. They pursued a strategy of theoretical model-building, piecing together what was known about DNA's chemical components into a viable three-dimensional structure. Their approach was in contrast to the painstaking experimental work being conducted at King's College London by Maurice Wilkins and Rosalind Franklin. Franklin, an accomplished X-ray crystallographer who had honed her skills in Paris, joined King's in 1951 to work on the DNA problem. A misunderstanding from the outset soured her relationship with Wilkins; he viewed her as an assistant, while she believed she had been given sole charge of the DNA project. This difficult working relationship would have profound consequences.

Franklin's meticulous work soon yielded crucial results. By carefully controlling the hydration of her DNA samples, she was able to produce X-ray diffraction images of unprecedented clarity. These images revealed two distinct forms of DNA, a drier 'A' form and a wetter 'B' form. In May 1952, Franklin and her PhD student, Raymond Gosling, produced an image of the 'B' form that was particularly revealing. Known to history as "Photograph 51," its distinct X-shaped pattern was a clear indicator of a helical structure. While Franklin continued her cautious, data-driven analysis, the Cambridge duo were growing impatient. Their first attempt at a model, a triple helix with the phosphate backbone at the core, was a failure, quickly proven wrong by Franklin when they presented it to the King's College team in late 1951.

A Glimpse of the Helix

The breakthrough for Watson and Crick came through their access to the experimental data from King's College, a matter of enduring controversy. In early 1953, Maurice Wilkins, without Franklin's permission or knowledge, showed Photograph 51 to James Watson. For Watson, the image was a revelation, providing the vital evidence of a double helix that he and Crick needed to refine their model. Around the same time, Crick obtained a copy of an internal report from King's College which contained Franklin's detailed measurements and analysis of the DNA molecule. Armed with this critical, uncredited data, Watson and Crick were able to deduce the final pieces of the puzzle. Watson's key insight, in the spring of 1953, was that the four organic bases—adenine (A), guanine (G), cytosine (C), and thymine (T)—must be linked in specific pairs: A with T, and G with C. This pairing rule explained the constant width of the DNA molecule and, crucially, suggested a mechanism for its replication.

With this final piece in place, they rapidly constructed their iconic model: a right-handed double helix, resembling a twisted ladder. The two sugar-phosphate backbones formed the sides of the ladder, while the paired bases formed the rungs. On 25 April 1953, their findings were published in a modest, 900-word paper in the journal *Nature*, a publication that would fundamentally change biology. In the same issue, supporting papers from Wilkins' and Franklin's teams were also published, providing the experimental evidence for the Cambridge model. The original announcement of the discovery was made by Sir Lawrence Bragg, the director of the Cavendish Laboratory, at a conference in Belgium on 8 April 1953, though it went unreported by the press at the time.

An Architect of Modern Biology

The discovery of the double helix was almost immediately recognised as a monumental achievement. In 1962, Watson, Crick, and Maurice Wilkins were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine "for their discoveries concerning the molecular structure of nucleic acids and its significance for information transfer in living material". Rosalind Franklin was not included. She had died of ovarian cancer in 1958 at the age of 37, and the Nobel Prize is not awarded posthumously.

Watson's career after the Nobel Prize was marked by significant influence as a scientist, administrator, and author. He joined the faculty at Harvard University in 1955, where his laboratory helped demonstrate the existence of messenger RNA (mRNA), a key molecule in the process of protein synthesis. In 1965, he published the textbook *Molecular Biology of the Gene*, which became a standard-setting text for a generation of biology students. In 1968, he took on the directorship of the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) on Long Island, New York. He transformed the small, financially struggling institution into a world-leading research centre, focusing its efforts on cancer research and making it a global hub for molecular biology. He served as its director and later president for 35 years.

Perhaps his most significant post-Nobel contribution was his role in the Human Genome Project. From 1988 to 1992, Watson headed the project at the US National Institutes of Health (NIH), successfully launching the international effort to map and sequence all the genes in the human chromosomes. He established the Ethical, Legal, and Social Issues (ELSI) programme to address the societal implications of the research. He resigned from the project in 1992 following disagreements with the NIH director over the patenting of genetic material.

The Unravelling of a Reputation

In 1968, Watson published *The Double Helix: A Personal Account of the Discovery of the Structure of DNA*. The book was a bestseller, offering a candid, gossipy, and highly personal view of the scientific process that was unusual for its time. It portrayed the discovery as a thrilling race, filled with ambition and rivalry. However, the book was deeply controversial from the outset. Both Francis Crick and Maurice Wilkins strongly objected to its publication, with their initial publisher, Harvard University Press, dropping the book as a result. A key point of contention was Watson's depiction of Rosalind Franklin, whom he often referred to dismissively as "Rosy". His portrayal was widely condemned as sexist and misleading, caricaturing a brilliant scientist as a difficult and uncooperative subordinate. He described her as unattractive and someone who did not emphasize her feminine qualities, a characterisation that cemented a distorted public image of Franklin for decades.

This willingness to provoke was a harbinger of a more destructive pattern in his later life. Over the years, Watson made a series of offensive public statements on a range of subjects. In 2000, he suggested a link between skin colour and sex drive, claiming, "That's why you have Latin lovers." He also made comments widely seen as sexist, suggesting that having women in labs makes work "more fun for the men" but that they are "probably less effective". He told a newspaper that if a gene for homosexuality were found, a woman should be allowed to have an abortion if she did not want a gay child.

The Final Exile

The turning point that led to his public ostracism came in 2007. In an interview with *The Sunday Times Magazine*, Watson stated he was "inherently gloomy about the prospect of Africa" because "all our social policies are based on the fact that their intelligence is the same as ours – whereas all the testing says not really". The remarks, which suggested a genetic basis for differences in intelligence between racial groups, were immediately and widely condemned as racist and scientifically baseless. The ensuing international furor forced Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory to suspend him from his position as chancellor. Less than two weeks later, he announced his retirement, ending a nearly 40-year career at the institution he had built.

Although he issued an apology, the damage was irreparable. His reputation as a pioneering scientist was irrevocably tarnished. The final severing of ties came more than a decade later. In a 2019 television documentary, when asked if his views on race and intelligence had changed, Watson replied, "No, not at all." He went on to state that the difference in average IQ test results between black and white people was, in his view, genetic. In response, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory issued a statement calling his remarks "reprehensible" and "unsupported by science." The laboratory revoked his remaining honorary titles, including chancellor emeritus and honorary trustee, severing all remaining connections with him. The institution that had been his life's work cast him out completely. James Watson died on 6 November 2025, at the age of 97, in hospice care following a brief illness.

Conclusion

James Watson's legacy is one of profound and unsettling contradiction. On one hand, he was a co-discoverer of the double helix, a scientific achievement that transformed our understanding of life itself and opened the door to innovations in medicine, agriculture, and forensics. His leadership at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory and his role in launching the Human Genome Project further cemented his status as a key architect of modern biology. On the other hand, his career was marred by a persistent pattern of offensive and prejudiced remarks that were ultimately his undoing. His public statements were not merely controversial; they were condemned by the scientific community as baseless and deeply hurtful. The man who helped decipher the elegant code of human heredity repeatedly promoted crude, unscientific theories about human difference. His final years were spent in a state of professional exile, a pariah in the very world he had helped to create. The story of James Watson serves as a powerful reminder that scientific genius and moral insight are not intrinsically linked, and that the pursuit of knowledge does not grant immunity from the fundamental tenets of human decency.

References

-

Current time information in New York, NY, US

This source was not used in the article as it only provides the current time and is not relevant to the biographical content.

-

James Watson - Wikipedia

Provides comprehensive biographical details, including birth and death dates, education, key career milestones such as the Nobel Prize, his role at CSHL and the Human Genome Project, and the final revocation of his honorary titles.

-

James Watson, co-discoverer of the shape of DNA and Nobel Prize winner, dies at 97

Confirms Watson's death at 97, his 1962 Nobel Prize, his role at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, and the controversies surrounding his remarks on race, leading to the revocation of his titles in 2019.

-

James Watson: DNA pioneer censured for offensive race remarks dies | UK News

Reports on Watson's death, his 1962 Nobel Prize, and the condemnation he faced for his offensive remarks, including his suspension and later resignation from CSHL and the reaffirmation of his views in a 2019 documentary.

-

James D. Watson, scientist who co-discovered DNA's double-helix shape, dies at 97 - PBS

Details the significance of the DNA discovery, its impact on various fields, and the ethical questions it raised. It also quotes Francis Collins on Watson's hurtful remarks and notes his censure for saying Black people are less intelligent.

-

James Watson | Biography, Nobel Prize, Discovery, & Facts | Britannica

Provides key biographical information, including his birth and death dates, education at the University of Chicago, the 1962 Nobel Prize, his role in the Human Genome Project, and his 2007 resignation from CSHL following controversial remarks.

-

James Watson, Who Helped Discover DNA's Double-Helix Structure, Dies at 97

Confirms Watson's death at age 97 in hospice care following a brief illness, as stated by his son and confirmed by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory.

-

James D. Watson - Nobel Prize Winners - Biography

Outlines Watson's career, including the discovery of the double-helix, his 1962 Nobel Prize, his leadership of the Human Genome Project, and the publication of his book 'The Double Helix' in 1968.

-

Maurice Wilkins - Wikipedia

Details Maurice Wilkins' role in the DNA discovery, his early X-ray diffraction work at King's College London, and the tensions that arose with Rosalind Franklin.

-

Rosalind Franklin - Wikipedia

Provides information on Rosalind Franklin's career, her crucial work on DNA at King's College London, the disagreement with Wilkins, and her move to Birkbeck College.

-

The structure of DNA: How Dr Rosalind Franklin contributed to the story of life | Feature from King's College London

Explains Rosalind Franklin's critical contribution, including her creation of Photograph 51, her discovery of the A and B forms of DNA, and the publication of her paper alongside Watson and Crick's.

-

Maurice Wilkins | King's College London

Confirms Wilkins' role in the DNA discovery, his work with Ray Gosling, Franklin's contribution with 'Photograph 51', and the awarding of the 1962 Nobel Prize, noting Franklin's ineligibility due to her death.

-

Giants in genomics: Maurice Wilkins

Describes the misunderstanding between Wilkins and Franklin, and crucially notes that Wilkins showed one of Franklin's X-ray photographs to James Watson, which provided vital information for the double helix model.

-

Maurice Wilkins - DNA from the Beginning

Provides biographical details on Maurice Wilkins, his work on the Manhattan Project, his move to King's College, and his use of X-ray diffraction to study DNA.

-

Rosalind Franklin: The DNA Helix Pioneer - KCAS Bio

Highlights Franklin's pioneering work in X-ray diffraction, specifically 'Photo 51' taken with Raymond Gosling in 1952, and notes that her contribution was not fully recognized at the time.

-

Maurice Wilkins | Research Starters - EBSCO

Summarizes Maurice Wilkins' career, his contribution to the Manhattan Project, his transition to biophysics, and his crucial X-ray diffraction work on DNA at King's College London.

-

Watson and Crick: Controversy, Immodesty, DNA, and Books.

Details the controversy surrounding Watson's book 'The Double Helix', including objections from Crick and Wilkins, its initial rejection by Harvard University Press, and its sexist and dismissive portrayal of Rosalind Franklin.

-

Rosalind Franklin and the DNA Double Helix - LOST IN HISTORY

Explains how Franklin's work with Raymond Gosling produced high-resolution photos of DNA, and notes that Watson and Crick did not acknowledge her contribution in their initial paper, though she published in the same issue of *Nature*.

-

Rosalind Franklin | Biography, Facts, & DNA - Britannica

States that Franklin's work established that the DNA molecule existed in a helical conformation and laid the foundation for Watson and Crick's 1953 model.

-

James Watson - DNA from the Beginning

Provides biographical details on Watson, including his early education, the influence of Schrödinger's book, his PhD under Luria, and the publication of 'The Double Helix' in 1968.

-

Giants in genomics: James Watson

Details Watson's move to the Cavendish Laboratory, his meeting with Francis Crick, his leadership of the Human Genome Project, and his resignation over the issue of gene patenting.

-

James Watson, who helped unravel genetic blueprint for life, dies at 97 - The Washington Post

Confirms Watson's death and provides context on the 1962 Nobel Prize, noting that Franklin had died in 1958 and was ineligible. Also covers his career at Harvard and CSHL.

-

James D Watson, who co-discovered DNA's twisted-ladder structure, dies aged 97

Reports Watson's death, his 1962 Nobel Prize, his leadership roles at CSHL, and details the 2007 and 2019 controversies over his remarks on race and intelligence, which led to his suspension and the eventual revocation of his titles.

-

Francis Crick, Rosalind Franklin, James Watson, and Maurice Wilkins | Science History Institute

Describes the context of the discovery, the controversial nature of Watson's book 'The Double Helix', his unkind portrayal of Franklin, and the revocation of his titles by CSHL in 2007 and 2019 for his racist remarks.

-

James Watson, co-discoverer of DNA's double-helix shape, dead at 97 | CBC News

Confirms Watson's death and notes his reputation was tarnished by his comments and his willingness to use others' data. It specifically mentions the 2007 and 2019 remarks on the intelligence of Africans.

-

In remembrance of Dr. James D. Watson - Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory

An official statement from CSHL detailing Watson's contributions, including his influential textbooks, his leadership of the Human Genome Project, and the laboratory's decision to sever ties with him in 2020 over his remarks on race.

-

DNA Pioneer James Watson Loses Honorary Titles Over Racist Comments

Details Watson's history of controversial comments on race, gender, and sexuality, including his 2007 remarks and his sexist portrayal of Rosalind Franklin in 'The Double Helix'.

-

James Watson, scientist who co-discovered DNA's double helix, dies at 97 - Ynetnews

Reports on Watson's death and highlights how his reputation was tarnished by racist comments. It mentions the 2007 and 2019 incidents and the criticism of his book 'The Double Helix'.

-

James D. Watson | Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory

Provides an official CSHL biography detailing his leadership roles (Director, President, Chancellor), his revitalization of the laboratory, and his directorship of the Human Genome Project at the NIH.

-

Examining James Watson's Controversial Statements on Race. | by YAREK GUY - Medium

Focuses specifically on Watson's controversial statements on race and intelligence, detailing the 2007 interview where he claimed Africans have lower intelligence and the subsequent condemnation from the scientific community.

-

James Watson: The most controversial statements made by the father of DNA

Catalogs Watson's most controversial statements, including his 2007 remarks on race and intelligence, his 2019 reaffirmation of those views, and his comments on skin colour, libido, and women in science.

-

The Double Helix - Wikipedia

Provides background on the publication and reception of Watson's book, noting the initial objections from Crick and Wilkins that led Harvard University Press to drop it, and the criticism of its sexist portrayal of Rosalind Franklin.

-

James Watson Cause of Death: DNA Pioneer Dies at 97 After Long Illness - Bangla news

Confirms Watson's death on November 6, 2025, at age 97 under hospice care, suggesting natural causes. It also notes his health had declined since a 2018 car accident.

-

Story Behind DNA Double Helix Discovery Gets New Twist - VOA

Discusses the controversy around the discovery, specifically how Watson and Crick relied on research from Franklin's lab without permission, including Photograph 51 and data from a lab report.

-

James Watson's The Double Helix: Inaccurate and Insightful - Campus Writing Program

Analyzes the historical inaccuracies in 'The Double Helix', particularly the 'unsavory characterization' of Rosalind Franklin, whom Watson misleadingly framed as a belligerent assistant and referred to as 'Rosy'.

-

James Watson, Nobel Prize winner and DNA pioneer, dies - Los Angeles Times

Confirms Watson's death and describes him as a 'semi-professional loose cannon' whose racist views made him a pariah. It also notes the controversy over his treatment of Franklin in 'The Double Helix'.